An Audacious Arrangement

An Audacious Arrangement

When state and community leaders assembled to break ground on Maryland’s largest affordable-housing project in September 2019, their motivations behind the endeavor were clear. Prince George’s County Executive Angela Alsobrooks said at the ceremony, “Seniors are the bedrock of our community, so we are Prince George’s Proud to support this project that will provide high-quality and affordable housing for Prince George’s County seniors.”

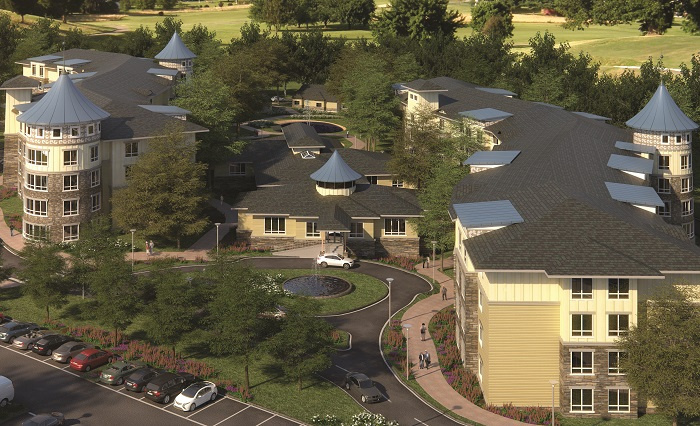

Called Woodlands at Reid Temple, the housing development is the realization of a vision championed by nearby Reid Temple A.M.E. Church and is a public/private partnership between the state of Maryland and local businesses. With a total of 252 units aimed at residents aged 62 and older who earn 70 percent or less of the area median income, one could use the word bold, maybe even audacious, to describe every aspect of this project.

This is particularly true when looking at the construction of the project’s three buildings. With two long, twisting buildings that flank an unusual central clubhouse, nothing about the buildings’ design or erection was simple or straightforward. Add in an incredibly aggressive schedule, and the structural framing presented an impressive challenge for Bruce Jones Contracting (BJC) and Shelter Systems Limited (Shelter).

A Well-Established Partnership

Working with JCC, BJC led the bid for the framing, knowing that Shelter would provide the roof and floor trusses for the project. “We’ve worked hard to cultivate a close relationship with Bruce Jones over the years,” says Ryan Hikel, sales manager for Shelter. “Our skillsets fit together perfectly. We do roofs and floors, but don’t do walls. They do wall panels and are expert framers. We mesh very well on projects.”

Both BJC and Shelter also had a good working relationship with the project’s general contractor (GC), Whiting-Turner, who operates throughout the country but have their headquarters in Baltimore. “We both got involved at the ‘napkin’ stage of the project,” says Ryan. “Working alongside the GC, we talked about what framing approaches would be most cost-effective, and what would go together best on the jobsite.” Jason Valis, general manager for BJC, was also quick to recognize the project’s engineer of record (EOR), Ronald Wolfman, saying, “he was an instrumental part of the team who was always available to take a call to work out any issue.”

All the players expressed some initial anxiety about the aggressive construction schedule given the sheer size of the buildings, and everyone saw up-front collaboration on the design as being crucial to getting it done on time. There simply wasn’t room for any significant set-backs or delays once construction began. “Initially, Whiting-Turner wanted to hire two framing contractors to get the job done, each working on a separate building,” says Bruce Jones, founder of BJC. “We convinced them it would go more quickly and smoothly if they let the two of us do it all.”

One of the biggest initial challenges was going through all of the geometry in the buildings. The architects, Wien-cek + Associates, envisioned two enormous buildings whose footprints flowed with the topography of the site and provided unobstructed views of the natural woodlands and golf course surrounding it. “The walls were originally designed to be stick-built, but when the GC told us it would all be panelized we were completely on board,” says Michael Wienek, the owner of the architectural firm. “Panelizing didn’t change the exterior of the buildings to any great degree, but 90 percent of the internal wall layouts ended up being altered slightly to standardize the individual units.”

“Bob Cleckner, the GC’s lead on this project, worked tirelessly with us on finalizing the building design,” says Jason. “As we worked through the design, they were really open to our recommendations on changes to make the building easier to construct.”

Construction of the buildings got underway, even as they worked through these changes. “We had boots on the ground with the drawings only 50 percent complete,” says Bruce. Again, the tight timetable required a fast start, but BJC and Shelter knew from experience that their close collaboration, as well as the willingness of the architect and GC to incorporate their suggested changes, would allow them to finish the plans effectively on the go. “When it came to the framing, our version of the plans often became the drawings everyone worked off of in the field because they contained the most current design information due to changes, RFIs, and ASIs,” says Bruce.

Unexpected Disruption

One thing no one on the project anticipated on the front end was the impact the COVID-19 outbreak would have on everyone’s ability to continue making progress. “Right in the middle of the design phase, we all had to leave the office and work remotely,” says Rob Grabus, Shelter’s lead designer on the project. “Fortunately, we were able to transition to daily Zoom meetings with Bruce Jones and Whiting-Turner and keep the changes moving forward.”

BJC estimated they needed 220 trailers of wall panels, roof and floor trusses, and field framing lumber for the entire project. The jobsite only had one entrance and exit, and because of the number of contractors that needed to be engaged during construction, every truck delivery had to be scheduled far in advance. “It was difficult for everyone; if you didn’t register a truck ahead of time or missed your window you wouldn’t be allowed on the jobsite,” says Jason. It also meant that every crane pick had to be scheduled, and the roof trusses, wall panels, and floor trusses all had to get installed according to the timetable. “We had to schedule everything at least four weeks ahead for every delivery and crane day,” he adds. “Several days we had multiple cranes running at the same time.”

So things got particularly challenging when Tom Wolf, the governor of Pennsylvania, announced on Friday, March 13, that he was issuing an executive order for all non-life-sustaining businesses to be closed on Monday, March 15. “That was a problem for our wall panel production,” says Jason. “While most of our construction projects were located in Maryland like this one, and Virginia and D.C., our panel manufacturing is done in Pennsylvania. Our customers needed us to keep working, but our geographical location prevented us from easily doing so.”

When BJC’s wall panel facility received the governor’s order to close with essentially two days’ notice, it threatened to cause a huge disruption to the construction schedule. “We had to call our entire team in over the weekend and load and move over 20 truckloads of wall panels and material from our property in Pennsylvania,” says Bruce. “We were very fortunate and thankful Shelter let us temporarily stage those trailers at their facility in Maryland until the jobsite was ready for them.”

Fortunately, a week later, BJC obtained a waiver to re-open their panel facility. “We didn’t miss a beat and I can’t say enough about the incredible teamwork it took to pull that off,” says Jason.

Jobsite Coordination

Another unintended consequence of COVID-19 was the impact it had on how jobsites operated. “Normally, you’d have the GC leadership on site in a trailer, coordinating the different trades and working through issues,” says Jason. “But with COVID, the trailer was empty and sometimes the GC leadership was on site coordinating things and sometimes we were actually coordinating things on the ground. It was a unique situation because of the safety precautions in place. Everyone had to get creative in their communication on the jobsite; a lot of our coordination meetings became virtual, practically overnight.”

Each of the two main buildings were broken up into three, 40,000-square-foot sections, with the turrets erected separately. The clubhouse was purposely built last to enable all the trades full access to the main buildings as long as possible. “We had 50-60 carpenters on the ground most days,” says Jason. “We framed 17,000 square feet of production each week. In total, it took us 14 weeks to frame the two main buildings, installing more than ten miles of wall panels.”

Those numbers are even more impressive when you take into consideration that the team accomplished the feat in the middle of a Northeastern winter, at the height of the initial pandemic outbreak. “I think most of the credit can go to the fact that we had put so much work into the plans up front and continued to work so closely together on the changes throughout construction,” says Jason. “Many times we’d be sitting down in the GC’s trailer with one of the other trades, working through the drawings. Because of the knowledge we gained through the up-front design process we were able to help the other MEP trades coordinate and avoid potential clashes and conflicts before they started in the field.”

”Because of the knowledge we gained through the up-front design process we were able to help the other MEP trades coordinate and avoid potential clashes and conflicts before they started in the field.”

Intermediate BIM

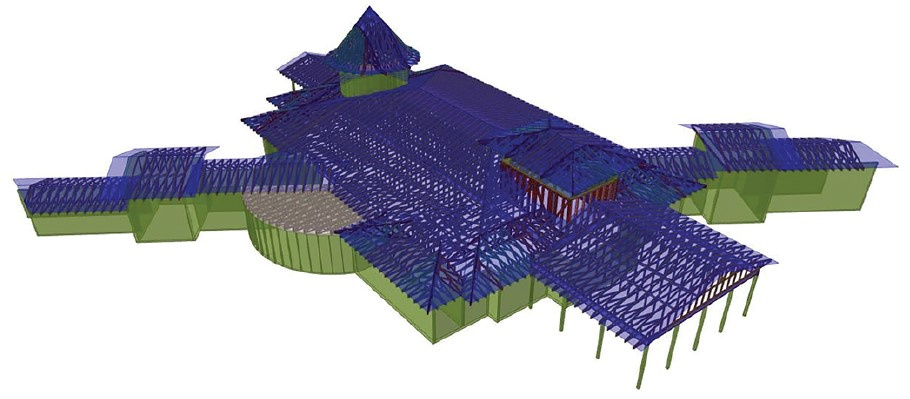

While BJC and Shelter didn’t utilize a full building information modeling (BIM) approach like Shelter had, for example, on the Boston Clippership Wharf project, they did the next best thing. “We weren’t doing clashes and conflicts with the other subs ahead of time but our two companies have been going through drawings together for years using CAD,” says Ryan. “Our coordination allows us to work out a lot of issues in 3D ahead of time and also help the other trades, too.” For instance, they shared the CAD drawings with the masonry contractor and were able to replace some of the concrete walls with wood construction.

All that CAD work was particularly crucial when it came to the central clubhouse. “There were a lot of unusual ceiling profiles, including a cupola in the front and a raised central section in the back,” says Rob. Those two central sections utilized post-and-beam construction. One instance of the benefits of using CAD was that Paul Dietz, BJC’s wall panel designer, was able to locate the exact location of each of the wet-set post bases and provide them to the concrete contractor prior to installation.

The rest of the building required a great deal of geometry beyond just the roof. “There wasn’t more than 20 feet of straight wall anywhere in that clubhouse,” laughs Paul. He and Rob worked closely through every element of the complex building. Whenever they identified a necessary change, they would jump on a Zoom call with the GC, architect, and engineer. “It’s a great feeling when you get to work with an architect and a structural engineer who trust the framer and the component manufacturer, let them do their jobs, and actually incorporate their input in a meaningful way,” says Rob. “They were always open to suggestions on how to build it better.”

“What was also interesting about this project was the wall panel designs drove the whole project,” says Ryan. Jason agrees, “We needed to keep the project moving quickly. The foundation drove the walls on the first floor, which in turn drove the floor trusses, and so on.” In essence, Shelter used the wall panel layouts to design the floor trusses for the next floor. Again, as issues arose, BJC and Shelter worked with the GC and the architect to get approval for changes quickly. “I can’t say enough about how great Bob was to work with on this project,” says Bruce.

Michael adds, “Everyone on this project was incredibly professional and great to work with. We always aim to push the envelope with affordable housing, and the only way the numbers really worked here was with an aggressive construction schedule. Thanks to the panelized walls, component framing, and great coordination between Whiting-Turner and their contractors, we were able to do everything we hoped to do on this project. We really hope to work with this group again on future affordable housing projects. This approach to framing makes a lot more projects financially viable.”

The Bottom Line

While a pandemic outbreak in the middle of an extremely aggressive construction schedule derailed many large-scale projects across the country, the symbiotic cooperation and up-front design work of BJC and Shelter, combined with a trusting and collaborative GC and architect, enabled Woodlands at Reid Temple to finish on schedule. “I know both BJC and Shelter were proud to be part of the construction team on this meaningful community project,” says Bruce. “It was a blessing to have everyone on the team be on the same page to give the owners a great final product.”

A ‘Flare’ for the Dramatic

One of the most distinctive elements of the Woodlands at Reid Temple are the large turrets at the front of the two main buildings. In keeping with their visual prominence, they presented some interesting design and construction challenges for Bruce Jones Contracting (BJC) and Shelter Systems Limited.

“The walls were originally called out to be stick framed, but we wanted to panelize them,” says Paul Dietz, BJC’s lead panel designer. “Rounded walls didn’t fit within our normal process, though, so we had to be creative.”

The first thing they did was use two layers of three-quarter-inch plywood, cut with a CNC machine, to make the top and bottom plates of the walls, as well as the window sills and wall blocking. “The window openings were interesting because, while the walls were rounded, the windows were flat, so the window sills had to be doubled up,” says Paul. “The outside sills were rounded to the outside wall profile; the inside sills were rounded to the inside wall profile and then square to the outside to match the window profile.”

To match up the wall panels with the floor trusses, Paul worked closely with Rob Grabus, lead designer on the project for Shelter. “Paul and I started with the turret radius from the architect and made sure we were both working from the exact same dimensions,” says Rob. Originally, LVL joists were called out to tie the turret floor framing to the building but the solid joists blocked some MEP paths. “So, I designed some open-webbed girder trusses that allowed the MEP to pass through.”

A steep-pitched roof with a dramatic flare topped each turret. Rob designed the roof with two girder trusses spanning the middle of the turret and mono trusses fanning out from each, and then used a third girder to tie the roof to the opening in the main building. “There were a lot of individual pitches in that roof profile, so I designed separate trusses for each pitch break,” says Rob.

Roof trusses were also used in an unusual way to create a flare at the bottom of each turret tower as it met the ground. “Bob from Whiting-Turner (the GC) actually had the idea to use a truss to create the flare,” says Paul. “We agreed that was a great plan, had Shelter build them, and anchored them to the walls once the turrets were framed.”

It may sound simple, but it required a great deal of foresight in the design given that the flare extended over three stories. “The radius and the geometry of the flare changed at each opening,” says Jason. “They did incredible design work on those turrets.” All of these little details played a big part in making the architect’s original concept a dramatic reality.