Don’t Confuse Revenue with Earnings

Don’t Confuse Revenue with Earnings

Component manufacturers (CMs) seeking acquisition or recapitalization (see definition in sidebar) will often call an investment banker (IB) for an initial consultation about the company’s value. It’s the role of the IB to represent that company, so the IB will ask: Have you thought about what your company is worth? Your bottom line?

This question can often expose any unrealistic expectation the CM owner may have about the company’s value. It’s not unusual for an owner to have a value in mind that’s higher than the market will bear. It’s human nature and a reflection of the pride the owner feels for growing a successful business. These conversations can get crossways, particularly if the CM responds to the valuation question by simply citing their revenue.

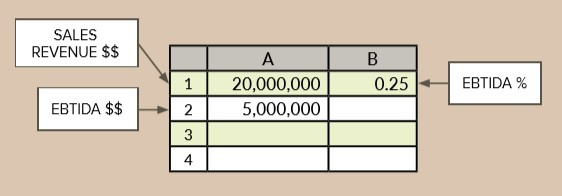

While a healthy top-line revenue is essential, and having millions of dollars to work with is desirable, possessing a large top-line is not the same as dropping a meaningful number of those revenue dollars to EBITDA and maximizing EBITDA as a percentage of sales (Figure 1). Those are the two Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that acquirers really focus on; let’s talk about why.

Recapitalization (“Recap”)

In an acquisition, a recapitalization is when the sellers of a company take shares in the new company (“newco”) created by the acquisition, instead of 100 percent of the value of their company in cash at the closing. In most acquisitions, the sellers of a company take a minority position in newco. This strategy is used for two reasons: one, it reduces the amount of cash the acquirers need to complete the transaction, and two, it allies the previous owners to the newco as vested partners to help with its growth.

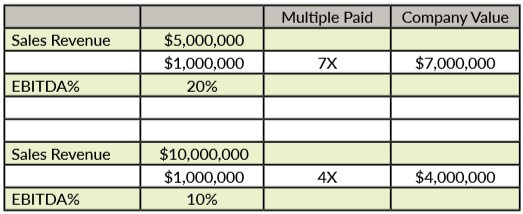

In an acquisition or recapitalization, the vast majority of CMs will be valued using a multiple of EBITDA, not a multiple of top-line revenue or a “discounted cash flow” method. As my last article explained, EBITDA is a more dependable proxy for how well the CM is at generating earnings. Further, the EBITDA percentage, no matter the company’s revenue, provides a good measure of how efficiently the company is making a profit.

How does this translate to a company’s value? A company with no EBITDA, one that’s just paying the bills from month-to-month, would be a book value sale; essentially, total assets minus intangible assets and liabilities. Conversely, a profitable CM would attain a sale price based on a multiple of EBITDA between 5X and 7X, depending on the company’s operations, automation, and EBITDA percentage. An underperforming company, as measured by its EBITDA percentage, may be valued at 4X or lower. We know these multiples apply to CMs from financial services data that report on acquisitions completed in the past 24 months.

For example, the 5X to 7X multiple of EBITDA would mean that a CM with $500,000 in EBITDA is worth between $2.5 and $3.5 million.

The amount actually paid in cash for the business can vary. If there is no recapitalization and no earnout, where payment is made over time, the seller gets “all cash at close.” If there is a recapitalization, the seller retains some percentage of his or her ownership, taking an equity interest (very often a minority position) in the new company formed by the acquisition. Recaps are often attractive because they reduce the amount of cash required for the acquirer to purchase the CM.

Your Sales Rep Is Pumped, But Are You?

As a business owner, how many times have you heard a sales rep say he or she is having a great week because of the large truss and wall panel order they just booked? And how many times have you murmured under your breath, after hearing the customer’s name, that the order might just break-even by the time the package is designed, discounts are applied, the components are transported to multiple jobsites, and then you wait 100 days to get paid?

Just like the salesman, when a CM owner cites his top-line revenue as the indicator of his value to the IB, he’s missing the bigger picture. The owner should also have an eye on the other business performance metrics that acquirers find most important when acquiring or investing in a business. When the IB is shopping the deal on the seller’s behalf, acquirers will surely want to know the top-line revenue figure, because it allows them to gauge the magnitude of the operation. However, they will then immediately scan the financial statement to find the unadjusted EBITDA, and the EBITDA percentage. Then they’ll turn their attention to at least four additional KPIs:

- Cost of goods sold (COGs): The financial statement should show the dollar amount, and expressed as a percentage of revenues.

- Gross profit: The dollar amount, and expressed as a percentage, a.k.a. gross profit margin, or GPM.

- Customer concentration for top 25 customers: Each expressed as a percentage of overall sales, along with the GPMs for each.

- Operating expenses (OPEX): The dollar amount, and expressed as a percentage.

Figure 1. The rate at which sale revenue contributes to EBITDA is expressed on a summary financial statement as “percent EBITDA.” In this example, the formula to calculate percent EBITDA would be =A2/A1, where A2 is the EBITDA dollars, and A1 is the revenue dollars.

EBITDA as an Indicator of Company Health

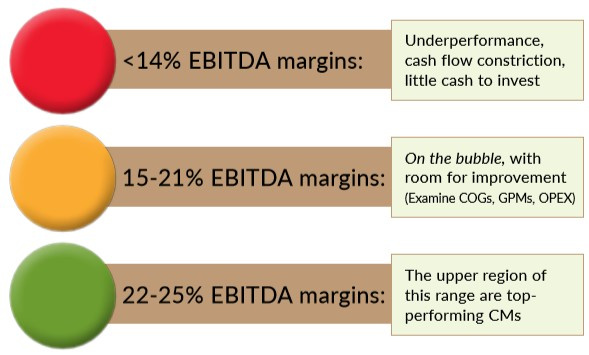

Let’s look at an example. For ease of math, if you have a top-line sales revenue of $5,000,000, and an EBITDA of $1,000,000, you have an EBITDA percentage of 20 percent (see Figure 2). This means that $0.20 out of every top-line revenue dollar is not spent on cost of goods sold (COGS) or operations (OPEX). EBITDA margins in the building material and building products industry vary widely. Some pure lumber dealers, with lots of low-margin commodity sales, can operate as low as five percent EBITDA. Well-run, non-specialty lumber dealer businesses can run 10-12 percent. (As revealed in their recent earnings calls and SEC filings, the publicly held US LBM’s adjusted EBITDA margin, as an example, is around seven percent.)

Figure 2. A $10,000,000 sales revenue CM is worth about half as much as a CM with $5,000,000 in revenue, due to its lower percent EBITDA performance, which drives down the multiple paid in an acquisition.

Figure 3. Sources: 1StWEST M&A and Ben Hershey, 4Ward Solutions Group

As companies move into offering higher-margin, valued-added services, which include engineering and design services (CMs are a perfect example of this), the EBITDA percentages climb well into the teens, especially if the operations are automated. (See Figure 3.)

Low EBITDA, Suppressed Value?

Most acquirers or investors today want to buy a CM for its EBITDA cashflow, but the company’s value is established by its EBITDA percentage. Accordingly, the EBITDA is by far the most-scrutinized figure on a summary financial statement.

That said, some acquirers or investors will look at a poor-performing company with a low EBITDA margin and they’ll look at the COGs, OPEX, and GPMs, to see if there are opportunities for improvement. For a company that is underperforming on the EBITDA line as a percent of revenue, an investor may acquire the company at a multiple of EBITDA that’s lower than the going rate (say 4X, not 6X). Then, under new ownership, they drive a higher EBITDA by improving COGs, OPEX, and GPMs, such as correcting an employee count that’s too high as a percentage of revenue, or squelching volume customer discounts that are killing GPMs. The latent value of an underperforming EBITDA may actually attract a certain class of investor to a deal instead of driving them away. They buy in at a multiple of current EBITDA, which they improve, thereby driving down the effective multiple they used to make the acquisition.

Keep KPIs in the Swim Lanes

What’s the best way for company owners to avoid the trap of suppressed valuation at the time of sale or recap? Make sure your KPIs are all performing well within the “swim lanes” for businesses of your size in your region. A great way to do this is participating in SBCA’s Financial Performance Survey (FPS) that offers comparison data by region and manufacturers’ size. In addition, focus on EBITDA performance, both in dollar and percentage terms, because that’s what acquirers will really look at when they evaluate (and value) your business.